Non-Profit Research to Understand and Elevate the Volunteer Experience

Non-Profit Research to Understand and Elevate the Volunteer Experience

When you hear or read the phrase, “market research”, what comes to mind? For most it likely elicits mental images of large brands, slow timelines, and thoughts of huge project costs (we’d argue that it’s an investment and not a cost, but I digress). While true, larger research programs span hundreds of thousands of dollars; smaller projects can be as agile and affordable as you need them to be.

Enter Dog Aide, a non-profit organization in the Detroit area that helps dogs and their owners with varying levels of support made possible by their pool of passionate volunteers. Dog Aide cares about whether their volunteers are having a positive experience and about what they can do to make it enjoyable to grow their ranks. We crafted a research program aimed at just these very objectives, and it was a homerun experience for both parties.

This research was incredibly fun for us to carry out because we knew we would be making a big impact at a non-profit – we always aim to deliver recommendations that are attainable and can be transitioned quickly into action. Dog Aide has given us permission to share a few with you all, so here are some results that we found interesting and that could have a wider impact beyond the non-profit space:

Dog Aide’s varying volunteer pool (current volunteers, lapsed volunteers, and those yet to volunteer but signed up with the organization) prefers communications to come across different channels. Some of Dog Aide’s volunteers were finding out about opportunities too late because they simply didn’t check that particular communication platform regularly.

Implication for other categories: Your potential customers most likely won’t be reached with a single media vehicle – to maximize your reach and audience, you need to have multiple outlets of communication.

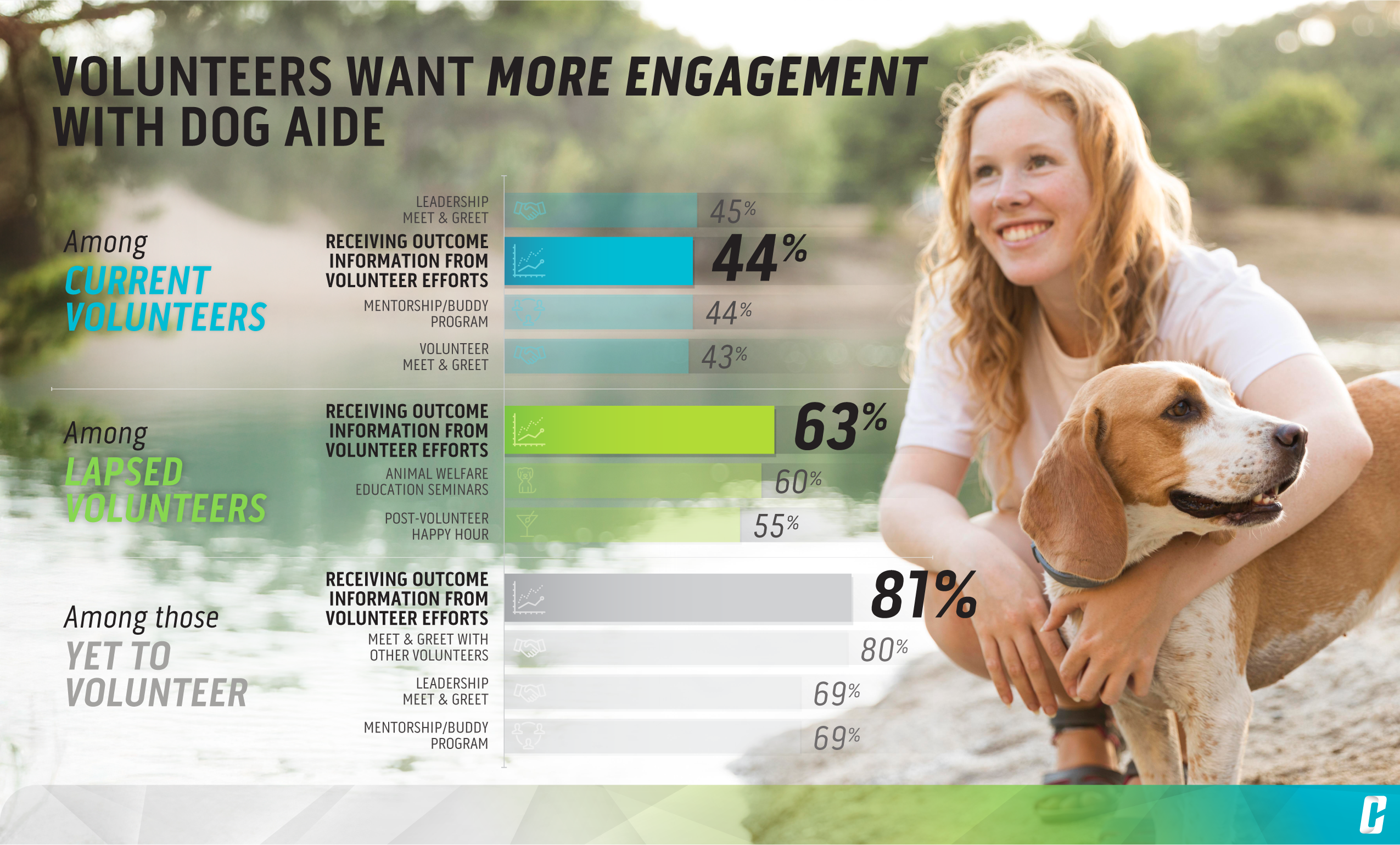

Dog Aide wanted to know how to reinforce and drive engagement with their volunteers and what we discovered was that regardless of the type of volunteer, everyone wanted to know the outcome or impact of their efforts:

Implication for other categories: Whether it be volunteers for a non-profit or your most stalwart brand champions, when people put extra effort and time into supporting a cause or product, they want to know if their blood, sweat, or tears made an impact. A great way to drive engagement with your brand or products is to show that you care about the time and effort people put in – how that manifests will vary greatly across categories and industries, but it’s still something that should be given some thought.

Implications for other categories: None! This is just an overall amazing number to see and if anything, other organizations should copy as much as they can to help drive their own engagement and sentiment.

Research doesn’t need to cumbersome or expensive – it can be far more attainable than you think. In our April Newsletter, we give some ideas and guidance on how to achieve actionable market research when you are part of a smaller organization or when you really need to stretch and make the most of a smaller budget. If a small non-profit organization can run meaningful and sound market research, so can you!

Andre Barroso

DIRECTOR, INSIGHTS & INNOVATION

CATAPULT INSIGHTS